T h e R o l e o f a n A l l i e d H e a l t h A s s i s t a n t

With an ageing population and a rise in chronic disease across the board, there is an ever increasing demand on the Australian healthcare

system and a widening gap between the availability of allied health workers such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists and the demand for their services. “Currently, seven per cent of the Australian workers are health care workers. If this amount remains constant, there will be a decrease in the ratio of health workers to the over 65 age group, more apparent in rural areas leading to poorer health outcomes” (Mercer-Moore, 2011). To reduce this gap and to be able to cope with any future healthcare needs the health workforce needs to adapt and be innovative as well as utilise “the use of the existing skills of the current professional and assistant workforces” (The Workforce, 2012. p.1). One such assistant workforce is the Allied Health Assistants.

Although Lizarondo (2010. P.143) states that “Allied Health Assistants (AHAs) are an emerging group in allied health practice with the potential to improve quality of care and safety of patients”, they have been working side-by-side with Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) for many years, often better known as Physiotherapy Assistant, Exercise Assistant, Therapy Aide or Therapy Assistant.

AHAs play an important role in providing high quality, patient-centred and efficient health care to patients who want to be actively involved in their own care. “To optimise the available workforce and achieve the right number and mix of personnel needed to provide high-quality care” (Dubois, 2009), tasks are allocated to AHAs through “role enhancement” and “role substitution”. This concept of extended scope practices allows AHPs to focus their attention on patients with more complex conditions and needs.

“In a specific health care context, role enhancement describes a level of practice that maximizes workers' use of in-depth knowledge and skills

(related to clinical practice, education, research, professional development, and leadership) to meet clients' health needs” (Dubois, 2009). New skills, proficiencies and practices are developed through increasing experience, continued professional growth and development as well as collaboration with colleagues from other disciplines. As such, role enhancement takes place within a person’s full scope of professional practice and does not include adding functions from other professions.

Expanding the healthcare workforce to cope with an ever increasing demand and to increase the workforce capability in shortage areas can be done by role substitution. “Role substitution involves extending practice scopes by encouraging the workforce to work across and beyond traditional professional divides in order to achieve more efficient workforce deployment” (Dubois, 2009), for example enrolled nurses working as AHAs.

AHAs work under the direction, guidance and supervision of an AHP to assist with the delivery of less complex clinical and non-clinical allied health services and support patient care within a specific area of practice. AHAs may have a generalist role, working across a number of allied health professionals such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy, podiatrists, dieticians and speech pathology, or they may be employed specifically to work with one allied health discipline. The term ‘allied health’ does not apply to medical health professionals such as doctors, surgeons, nurses or dentists.

AHAs implement care plans as devised by the AHP who conducted the patient assessment. Benefits of AHAs as part of the healthcare delivery can come in the form of more contact time for patients, freeing up time for higher level clinical practice for AHPs and creating both job and career opportunities for the local community.

With almost one quarter of the workers in the health and community services area having no formal qualification for the job they were doing at the start of this decade, the Community Services and Health Industry Skills Council (‘CS&HISC’) provided advice about future skill needs and

assisted in addressing the workforce reform agenda in Australia. One approach was to establish and maintain national vocational education and training (‘VET’) qualifications and occupational specific as well as generic competency standards in allied health assistance.

The newly created Certificate IV in Allied Health Assistance qualification as part of the Health 2007 Training Package covers health care

workers who provide therapeutic and program related support to and under the guidance of allied health professionals. It stated that supervision could be direct, indirect or remote and had to transpire within organisational requirements. However, in rural and remote areas supervision of the AHA in one specific stream could be delivered by video or teleconferencing with an AHP associated with that stream or through an allied health professional from another stream on site. Although the qualification was overall generic, six specialist streams were developed in the following areas physiotherapy, occupational therapy, podiatry, speech pathology, nutrition and dietetics and

community rehabilitation.

system and a widening gap between the availability of allied health workers such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists and the demand for their services. “Currently, seven per cent of the Australian workers are health care workers. If this amount remains constant, there will be a decrease in the ratio of health workers to the over 65 age group, more apparent in rural areas leading to poorer health outcomes” (Mercer-Moore, 2011). To reduce this gap and to be able to cope with any future healthcare needs the health workforce needs to adapt and be innovative as well as utilise “the use of the existing skills of the current professional and assistant workforces” (The Workforce, 2012. p.1). One such assistant workforce is the Allied Health Assistants.

Although Lizarondo (2010. P.143) states that “Allied Health Assistants (AHAs) are an emerging group in allied health practice with the potential to improve quality of care and safety of patients”, they have been working side-by-side with Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) for many years, often better known as Physiotherapy Assistant, Exercise Assistant, Therapy Aide or Therapy Assistant.

AHAs play an important role in providing high quality, patient-centred and efficient health care to patients who want to be actively involved in their own care. “To optimise the available workforce and achieve the right number and mix of personnel needed to provide high-quality care” (Dubois, 2009), tasks are allocated to AHAs through “role enhancement” and “role substitution”. This concept of extended scope practices allows AHPs to focus their attention on patients with more complex conditions and needs.

“In a specific health care context, role enhancement describes a level of practice that maximizes workers' use of in-depth knowledge and skills

(related to clinical practice, education, research, professional development, and leadership) to meet clients' health needs” (Dubois, 2009). New skills, proficiencies and practices are developed through increasing experience, continued professional growth and development as well as collaboration with colleagues from other disciplines. As such, role enhancement takes place within a person’s full scope of professional practice and does not include adding functions from other professions.

Expanding the healthcare workforce to cope with an ever increasing demand and to increase the workforce capability in shortage areas can be done by role substitution. “Role substitution involves extending practice scopes by encouraging the workforce to work across and beyond traditional professional divides in order to achieve more efficient workforce deployment” (Dubois, 2009), for example enrolled nurses working as AHAs.

AHAs work under the direction, guidance and supervision of an AHP to assist with the delivery of less complex clinical and non-clinical allied health services and support patient care within a specific area of practice. AHAs may have a generalist role, working across a number of allied health professionals such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy, podiatrists, dieticians and speech pathology, or they may be employed specifically to work with one allied health discipline. The term ‘allied health’ does not apply to medical health professionals such as doctors, surgeons, nurses or dentists.

AHAs implement care plans as devised by the AHP who conducted the patient assessment. Benefits of AHAs as part of the healthcare delivery can come in the form of more contact time for patients, freeing up time for higher level clinical practice for AHPs and creating both job and career opportunities for the local community.

With almost one quarter of the workers in the health and community services area having no formal qualification for the job they were doing at the start of this decade, the Community Services and Health Industry Skills Council (‘CS&HISC’) provided advice about future skill needs and

assisted in addressing the workforce reform agenda in Australia. One approach was to establish and maintain national vocational education and training (‘VET’) qualifications and occupational specific as well as generic competency standards in allied health assistance.

The newly created Certificate IV in Allied Health Assistance qualification as part of the Health 2007 Training Package covers health care

workers who provide therapeutic and program related support to and under the guidance of allied health professionals. It stated that supervision could be direct, indirect or remote and had to transpire within organisational requirements. However, in rural and remote areas supervision of the AHA in one specific stream could be delivered by video or teleconferencing with an AHP associated with that stream or through an allied health professional from another stream on site. Although the qualification was overall generic, six specialist streams were developed in the following areas physiotherapy, occupational therapy, podiatry, speech pathology, nutrition and dietetics and

community rehabilitation.

|

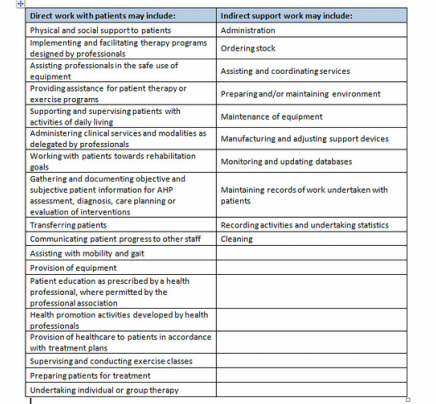

Role and Competencies of an AHA Although the role of an AHA can contain both clinical and non-clinical duties can be varied and flexible, in general AHAs work within clearly defined guidelines and boundaries. The range of duties an AHA can perform should be stated in the AHA position description and is often determined by: # The needs of the AHP delegating the duty to the AHA · # The types of services and programs delivered by the Allied team # The personal skills and abilities of the individual AHA The list beside, taken from the ‘Delegation and Supervision Framework for Allied Health Assistants’ states some of the direct and indirect activities that may be undertaken by an AHA: |

|

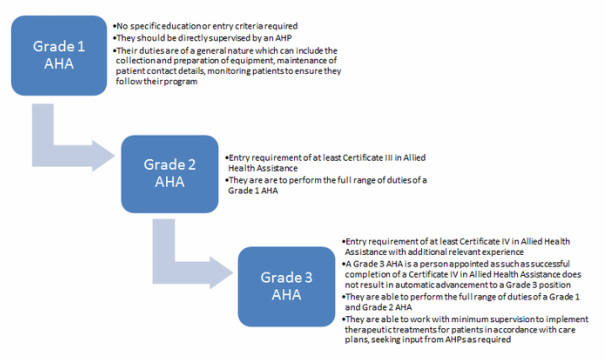

Before 2007 AHAs were classified either as qualified or unqualified. With the introduction of the nationally accredited Certificate III and IV in Allied Health Assistance qualification this classification changed, with AHAs now either being Grade 1, 2 or 3 depending on the level of AHA education and the level of supervision by an AHP required.

Full diagram of Grade 1, 2 & 3 duties, education-level entry criteria and career pathways can be found below. |

When an AHA has successfully completed all mandatory units and has acquired specific Allied Health discipline related

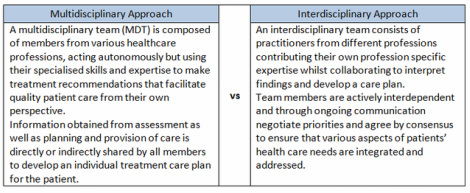

skills and knowledge they can specialise in that discipline. However, AHAs can also work more broadly across several disciplines as part of either a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinaryteam. Working in a multidisciplinary/ interdisciplinary team enables AHAs to participate in

rotations and gain experience working with practitioners of different disciplines. Being a member of either team it is important for the AHA to have good understanding of the overall treatment goals for each individual patient and as such it is imperative that the AHA is suitably involved in team meetings, patient handovers and reviews.

According to the Framework (The Workforce, 2012) “the role an individual AHA can play within multidisciplinary/ interdisciplinary team needs

to be based on the actual competencies the AHA holds”.

Common Competencies held by Grade 2 and 3 AHAs

Both the Certificate III and IV in Allied Health Assistance have seven identical units of competence which form part of the core (certificate

III) and the pre/co-requisites (certificate IV). As such, AHAs with either qualification will be competent in the following areas:

·

# Recognise healthy body systems in a healthcare context (anatomy & physiology)

# Use basic medical terminology

· # Maintain a high standard of patient service (which includes knowledge about ethical & professional work standards)

· # Assist with an allied health program

· # Assist with patient movement (manual handling and patient transfers)

· # Communicate and work effectively

· # Comply with infection control policies and procedures

Both qualifications also contain a unit of competence in regards to work health and safety which is at a basic level in the certificate III and

at a more standard level in the certificate IV. Full details for either qualification can be found when clicking on the button below.

AHAs can obtain competencies through:

# Formal training - successfully completing skills sets, short courses or electives as part of the certificate III or IV in Allied Health

Assistance

# Informal, in-house general or specific training

· # Experience gained in previous roles or through structured informal learning opportunities

· # Relevant programs delivered by professional associations or other organisations

Competencies obtained need to be documented so “that AHAs do not have to continually re-establish their competency attainment, when the AHP with responsibility for supervising them changes” (The Workforce, 2012. p.20)

skills and knowledge they can specialise in that discipline. However, AHAs can also work more broadly across several disciplines as part of either a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinaryteam. Working in a multidisciplinary/ interdisciplinary team enables AHAs to participate in

rotations and gain experience working with practitioners of different disciplines. Being a member of either team it is important for the AHA to have good understanding of the overall treatment goals for each individual patient and as such it is imperative that the AHA is suitably involved in team meetings, patient handovers and reviews.

According to the Framework (The Workforce, 2012) “the role an individual AHA can play within multidisciplinary/ interdisciplinary team needs

to be based on the actual competencies the AHA holds”.

Common Competencies held by Grade 2 and 3 AHAs

Both the Certificate III and IV in Allied Health Assistance have seven identical units of competence which form part of the core (certificate

III) and the pre/co-requisites (certificate IV). As such, AHAs with either qualification will be competent in the following areas:

·

# Recognise healthy body systems in a healthcare context (anatomy & physiology)

# Use basic medical terminology

· # Maintain a high standard of patient service (which includes knowledge about ethical & professional work standards)

· # Assist with an allied health program

· # Assist with patient movement (manual handling and patient transfers)

· # Communicate and work effectively

· # Comply with infection control policies and procedures

Both qualifications also contain a unit of competence in regards to work health and safety which is at a basic level in the certificate III and

at a more standard level in the certificate IV. Full details for either qualification can be found when clicking on the button below.

AHAs can obtain competencies through:

# Formal training - successfully completing skills sets, short courses or electives as part of the certificate III or IV in Allied Health

Assistance

# Informal, in-house general or specific training

· # Experience gained in previous roles or through structured informal learning opportunities

· # Relevant programs delivered by professional associations or other organisations

Competencies obtained need to be documented so “that AHAs do not have to continually re-establish their competency attainment, when the AHP with responsibility for supervising them changes” (The Workforce, 2012. p.20)

Grade 3 AHA Roles

The Delegation and Supervision Framework for Allied Health Assistants describes Grade 3 AHAs as having the following scope of practice:

·

# Grade 3 AHAs generally have a greater degree of independence and autonomy (within the pre-determined parameters of the care plan developed by an AHP) and as such have a larger scope to undertake work. However, there also needs to be clear and agreed responsibilities (between the AHP and AHA) to ensure the AHA keeps the AHP abreast of any clinical issues emerging around patient care, so the AHP can

actively monitor patient progress.

·

# The Grade 3 role can contain elements of responsibility for monitoring progress, against the pre-determined goals and treatment planning with the registered therapy professional supervising the AHA.

·

# While still being under the supervision and guidance of an AHP, a Grade 3 AHA may undertake some components of healthcare service delivery (for which an AHA has been trained and assessed as competent) in accordance with organisational policies and procedures. This may include some components of activities related to monitoring ongoing progress, treatment and coordination of care.

·

# The AHA will liaise closely with the AHP in regard to all activities and tasks especially in the absence of clearly prescribed parameters of practice established by an AHP. In some instances, where an AHA is working within their predetermined scope of delegation for a particular task it is reasonable for the AHA to initiate action to meet the patient’s immediate needs and provide timely notification to the relevant AHP in

accordance with organisational policies and procedures. This can only happen if it is clearly established up front between the AHA and the supervising AHP. In the absence of this, the AHA should consult with the AHP.

The Delegation and Supervision Framework for Allied Health Assistants describes Grade 3 AHAs as having the following scope of practice:

·

# Grade 3 AHAs generally have a greater degree of independence and autonomy (within the pre-determined parameters of the care plan developed by an AHP) and as such have a larger scope to undertake work. However, there also needs to be clear and agreed responsibilities (between the AHP and AHA) to ensure the AHA keeps the AHP abreast of any clinical issues emerging around patient care, so the AHP can

actively monitor patient progress.

·

# The Grade 3 role can contain elements of responsibility for monitoring progress, against the pre-determined goals and treatment planning with the registered therapy professional supervising the AHA.

·

# While still being under the supervision and guidance of an AHP, a Grade 3 AHA may undertake some components of healthcare service delivery (for which an AHA has been trained and assessed as competent) in accordance with organisational policies and procedures. This may include some components of activities related to monitoring ongoing progress, treatment and coordination of care.

·

# The AHA will liaise closely with the AHP in regard to all activities and tasks especially in the absence of clearly prescribed parameters of practice established by an AHP. In some instances, where an AHA is working within their predetermined scope of delegation for a particular task it is reasonable for the AHA to initiate action to meet the patient’s immediate needs and provide timely notification to the relevant AHP in

accordance with organisational policies and procedures. This can only happen if it is clearly established up front between the AHA and the supervising AHP. In the absence of this, the AHA should consult with the AHP.

References:

Dubois, C-A. & Singh, D. (2009). From staff-mix to skill-mix and beyond: towards a systemic approach to health rkforce management. Human Resources for Health 2009, 7:87. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/7/1/87

Human Resources Training Advisory Council Inc. (2012). Case study: allied health assistants—an emerging workforce. Northern Territory

Aboriginal Health and Community Services Workforce Planning and Development Strategy 2012. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.hstac.com.au/

Lizarondo, L. et all (2010). Allied Health Assistants and what they do: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2010;3:143-153

Mercer-Moore, S.Dr. (2011). Allied Health Assistants: A new wave of health workers. Australian Polity - Volume 2 (Number 1)

SARRAH (2014). Allied Health Assistants. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.sarrahtraining.com.au/site/index.cfm?display=143638

The Workforce (2012). Supervision and Delegation Framework for Allied Health Assistants. Department of Healthictoria). Finsbury Green Printers

Dubois, C-A. & Singh, D. (2009). From staff-mix to skill-mix and beyond: towards a systemic approach to health rkforce management. Human Resources for Health 2009, 7:87. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/7/1/87

Human Resources Training Advisory Council Inc. (2012). Case study: allied health assistants—an emerging workforce. Northern Territory

Aboriginal Health and Community Services Workforce Planning and Development Strategy 2012. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.hstac.com.au/

Lizarondo, L. et all (2010). Allied Health Assistants and what they do: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2010;3:143-153

Mercer-Moore, S.Dr. (2011). Allied Health Assistants: A new wave of health workers. Australian Polity - Volume 2 (Number 1)

SARRAH (2014). Allied Health Assistants. Retrieved April 2014 from: http://www.sarrahtraining.com.au/site/index.cfm?display=143638

The Workforce (2012). Supervision and Delegation Framework for Allied Health Assistants. Department of Healthictoria). Finsbury Green Printers