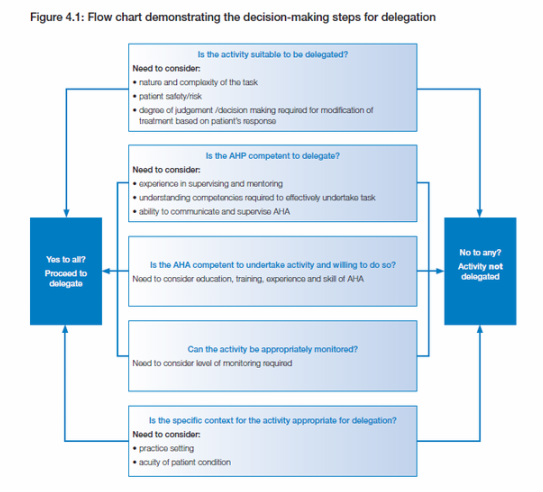

D E L E G A T I O N F L O W C H A R T - When is it appropriate to delegate

According to the Framework (The Workforce, 2012. p.22-23) there are a number of factors that determine if a task is appropriate to be delegated to an AHA, these being:

1. If the activity is suitable to be delegated, considering the scope of practice of the delegating AHP, whether it is within the scope of practice for an AHA, and if any legislation or regulatory requirements prevent the activity from being delegated

2. The competence of the AHP to delegate, considering whether the AHP has the appropriate skills, knowledge and ability to delegate, along with skills in supervising the activity, and the willingness to accept accountability for the performance of the task

3. The individual AHA’s depth of knowledge and skills, competence, attitudes and experience, considering the complexity of the task that the AHA is being asked to perform and their familiarity in undertaking the task, as well as the acuity and the complexity of the patient if it involves a clinical task. Key questions to ask include:

(a) Are the AHA’s competencies current?

(b) Is the AHA confident to undertake the activity?

(c) Does the AHA accept delegation of the task?

The AHA’s experience with the task to be delegated, their ability to undertake the task as well as their capacity to develop new skills. Has the AHA competently performed the particular task being delegated in the past, and if so, in what setting and circumstances? Specific instruction and a higher level of supervision from the AHP may be required if the AHA has limited to no experience with the task at hand.

4. The level of direct, indirect or remote supervision available to support the AHA and whether an activity can be appropriately monitored, considering all of the circumstances associated with undertaking the activity

5. The nature of the task in the specific circumstance, including the complexity of the task, the equipment to be used, the setting the

care is being provided in (for example, hospital or community), environmental factors, and any risks to the patient associated with undertaking

the task. In particular, it is important that the AHP considers the severity and complexity of the patient’s health condition, the stability of the patient and the complexity of care required.

1. If the activity is suitable to be delegated, considering the scope of practice of the delegating AHP, whether it is within the scope of practice for an AHA, and if any legislation or regulatory requirements prevent the activity from being delegated

2. The competence of the AHP to delegate, considering whether the AHP has the appropriate skills, knowledge and ability to delegate, along with skills in supervising the activity, and the willingness to accept accountability for the performance of the task

3. The individual AHA’s depth of knowledge and skills, competence, attitudes and experience, considering the complexity of the task that the AHA is being asked to perform and their familiarity in undertaking the task, as well as the acuity and the complexity of the patient if it involves a clinical task. Key questions to ask include:

(a) Are the AHA’s competencies current?

(b) Is the AHA confident to undertake the activity?

(c) Does the AHA accept delegation of the task?

The AHA’s experience with the task to be delegated, their ability to undertake the task as well as their capacity to develop new skills. Has the AHA competently performed the particular task being delegated in the past, and if so, in what setting and circumstances? Specific instruction and a higher level of supervision from the AHP may be required if the AHA has limited to no experience with the task at hand.

4. The level of direct, indirect or remote supervision available to support the AHA and whether an activity can be appropriately monitored, considering all of the circumstances associated with undertaking the activity

5. The nature of the task in the specific circumstance, including the complexity of the task, the equipment to be used, the setting the

care is being provided in (for example, hospital or community), environmental factors, and any risks to the patient associated with undertaking

the task. In particular, it is important that the AHP considers the severity and complexity of the patient’s health condition, the stability of the patient and the complexity of care required.

The Five Rights of Delegation

The Five Rights of Delegation

The Five Rights of Delegation

(Developed by the NCSBN – 1995)

1. The right task - one that is delegable for a specific situation/patient.

2. The right circumstances - where the appropriate patient setting, available

resources, and other relevant factors are considered.

3. The right person - delegating the right task to the right person to be performed in the right situation or on the right patient. Also, try to delegate something that the

other person likes to do! Know their strengths, weaknesses, preferences, and

motivations.

4. The right direction/communication - that includes clear, concise description of the task, including its objective, limits, and expectations, and supervision.

5. The right supervision (feedback) - which includes appropriate monitoring, evaluation, intervention, as needed, and feedback. The AHP cannot delegate a task and then disappear. They need to be available before, during, and after they delegate a task.

1. The right task - one that is delegable for a specific situation/patient.

2. The right circumstances - where the appropriate patient setting, available

resources, and other relevant factors are considered.

3. The right person - delegating the right task to the right person to be performed in the right situation or on the right patient. Also, try to delegate something that the

other person likes to do! Know their strengths, weaknesses, preferences, and

motivations.

4. The right direction/communication - that includes clear, concise description of the task, including its objective, limits, and expectations, and supervision.

5. The right supervision (feedback) - which includes appropriate monitoring, evaluation, intervention, as needed, and feedback. The AHP cannot delegate a task and then disappear. They need to be available before, during, and after they delegate a task.

http://neerajnayyar.com/2010/01

http://neerajnayyar.com/2010/01

Five reasons why the delegation process may fail

1) There was no accountability provided in the delegation process.

When delegating a task to an AHA a timeline for completion needs to be provided as well as a system of follow up, measures of accomplishment or benchmarks towards completion.

2) The AHP dumped the taskinstead of delegated it.

There’s an element of partnership in a good delegation process, where the AHP remains close enough to assure good progress and successful completion of the task through a monitoring and/or supervision process.

3) The AHA was not properly trained.

Assuming the AHA knows how to do the clinical or non-clinical task and can figure out their way on their own isn’t only naive it’s unfair. Good communication needs to take place before hand to make sure the AHA has the skills and knowledge to complete the task or the ability to learn along the way. This may involve the AHP spending more time in the early stages of a task to ensure completion is attainable by the AHA.

4) Adequate resources were not in place.

It’s difficult to expect an AHA to complete a task when the AHP has not been given the proper tools for the job. Sometimes a task has been delegated by the AHP too soon, before the AHA is ready, either personally, competently or in resources.

5) The wrong person was chosen for the task.

It is easy for a delegated task to fail if an AHA without the appropriate skills and knowledge has been selected. Selecting the best person from the start or reassigning when an improper fit is discovered is critical to assure completion of a task.

6) The Process was rushed

Sometimes delegation of a task is a last minute thought forgetting that delegation is a process and not an once off event which includes sequences of logical steps (see flow chart above).

1) There was no accountability provided in the delegation process.

When delegating a task to an AHA a timeline for completion needs to be provided as well as a system of follow up, measures of accomplishment or benchmarks towards completion.

2) The AHP dumped the taskinstead of delegated it.

There’s an element of partnership in a good delegation process, where the AHP remains close enough to assure good progress and successful completion of the task through a monitoring and/or supervision process.

3) The AHA was not properly trained.

Assuming the AHA knows how to do the clinical or non-clinical task and can figure out their way on their own isn’t only naive it’s unfair. Good communication needs to take place before hand to make sure the AHA has the skills and knowledge to complete the task or the ability to learn along the way. This may involve the AHP spending more time in the early stages of a task to ensure completion is attainable by the AHA.

4) Adequate resources were not in place.

It’s difficult to expect an AHA to complete a task when the AHP has not been given the proper tools for the job. Sometimes a task has been delegated by the AHP too soon, before the AHA is ready, either personally, competently or in resources.

5) The wrong person was chosen for the task.

It is easy for a delegated task to fail if an AHA without the appropriate skills and knowledge has been selected. Selecting the best person from the start or reassigning when an improper fit is discovered is critical to assure completion of a task.

6) The Process was rushed

Sometimes delegation of a task is a last minute thought forgetting that delegation is a process and not an once off event which includes sequences of logical steps (see flow chart above).